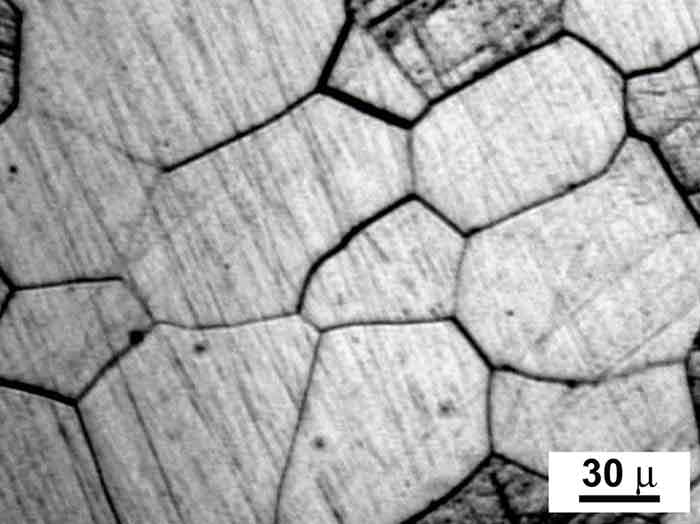

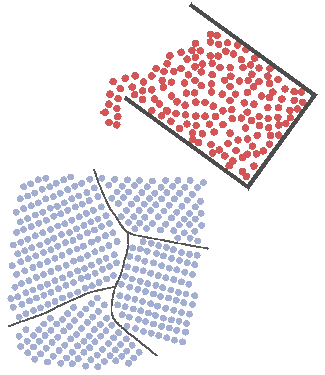

Traditional

Metals Have

Grain Boundaries

Typically, when a metal cools from a liquid to a solid, the atoms arrange themselves and grow into organized structures called grains. Where these grains intersect, a boundary is formed.

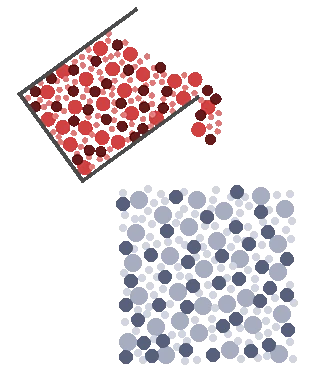

Amorphous

Metals are

Non-Crystalline

Liquidmetal was formulated to frustrate the movement of the atoms into the organized grain structure as the alloy cools. This results in a liquid-like atomic structure.

Stronger Than Other Alloys

Metals and alloys get their strength from the atomic bonds within the material. These bonds are weakened across a grain boundary due to dislocations and impurities. Liquidmetal does not have grain boundaries, so it is stronger than traditional engineering alloys such as stainless steel and Titanium.

The technological

evolution of

Amorphous Metals

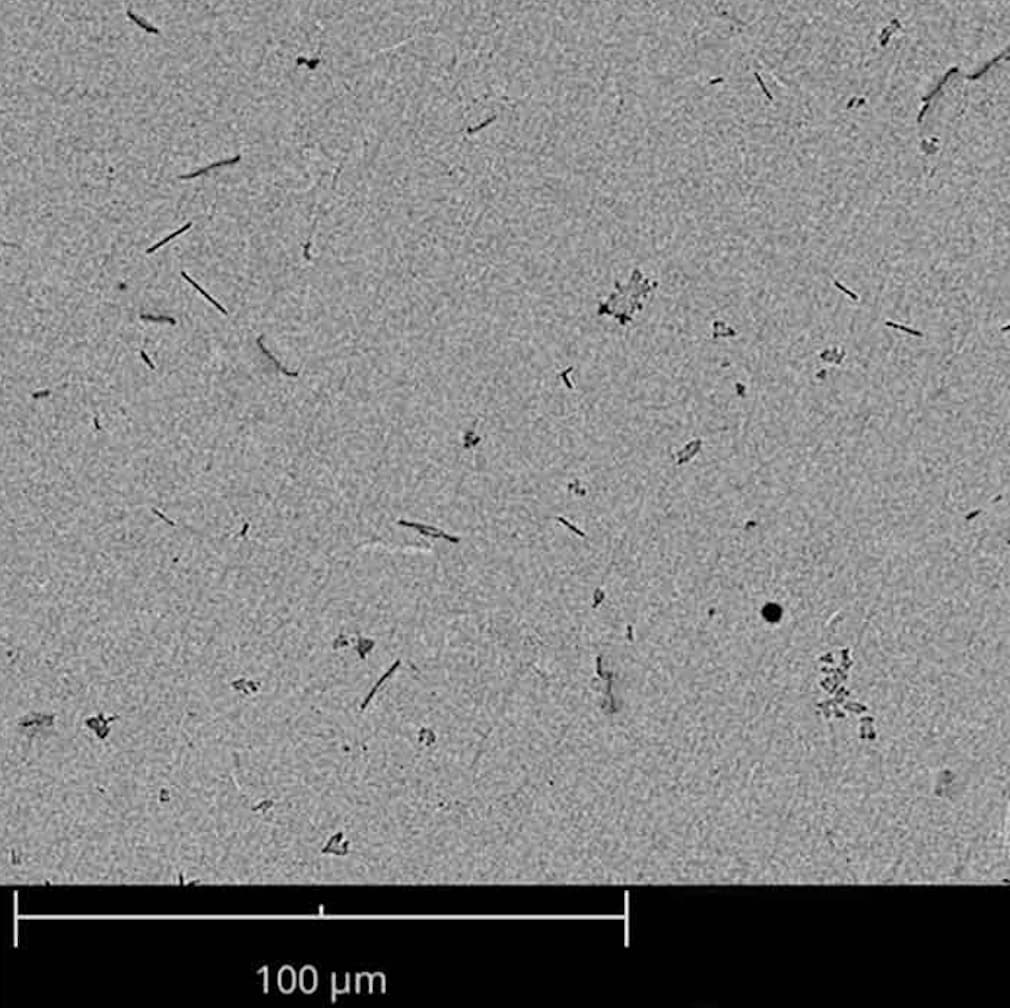

Early amorphous metals could only be manufactured in very thin ribbons, using a melt-spinning method to achieve the massive cooling rates required to defeat the crystallization that occurs when metal changes from a liquid to a solid.

R&D efforts began at NASA and Caltech, continuing on through many universities and Liquidmetal Technologies, to create alloys that will stay amorphous with much lower cooling rates.

Now the technology has driven past the limitation of only making thin ribbons. We can use an injection molding process to produce parts with larger cross sections. This allows us to manufacture useful parts across multiple industries.

Typical Part Sizes

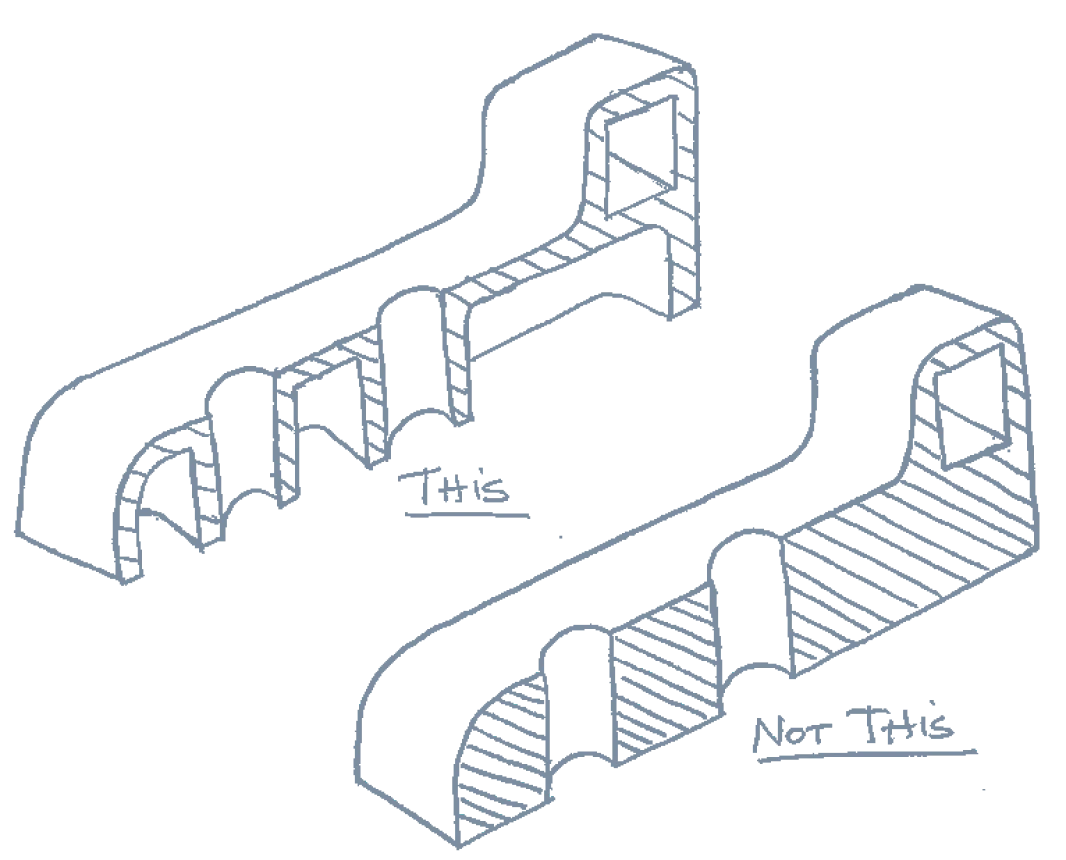

Being Amorphous is not entirely inherent in the alloy. The material still needs to cool relatively quickly. If the wall thickness of a part is too great, the material will not cool fast enough and begin to develop a crystalline grain structure.

Consideration must be taken to design your part with a wall section less than 2.5mm (0.10”). Many times, a part that was previously designed for CNC machining can be modified for our molding process by coring out the thick sections.